It's Time to Bring Unified Stream-Batch Processing Engines to Mass Adoption

Note: This article was translated from Chinese. Some technical terms and concepts may differ from the original English terminology.

This is an article that combines a decade of personal learning and growth to understand the development and iteration of unified stream-batch processing engines. The author, starting as an oblivious undergraduate student, observed the development of big data systems, gradually participated in it, and eventually became a committer in the Apache Flink community, following a spiral upward cognitive journey: starting with MapReduce batch processing, then developing machine learning libraries with Spark’s convenient and powerful batch processing capabilities; promoting Spark’s micro-batch-based real-time computing capabilities at Microsoft, then participating in Flink’s real-time computing development and promotion at Alibaba, moving from offline batch processing to real-time online processing, and after leaving Alibaba, promoting unified stream-batch processing engines within the company again.

As the elders say: personal struggle is certainly important, but it’s also necessary to align with the course of history.

Origin: First Glimpse of Apache Hadoop

More than ten years ago, the concept of big data was already very popular both domestically and internationally. Google’s three pillars - GFS, MapReduce, and BigTable - and their corresponding open-source implementations HDFS, Hadoop MapReduce, and HBase, became the hottest technical concepts at the time. Some even believed that big data was synonymous with Hadoop. At that time, my undergraduate thesis was about a rudimentary optimization of small file storage in HDFS. Since I would continue research in big data systems during my master’s program, I studied the relevant courses in the department in advance. I still remember the tedious complexity of implementing an inverted index for Wikipedia using MapReduce.

Of course, controversy followed fame. At that time, there was significant debate from database experts with “MapReduce: A Huge Step Backward.” Looking back now, to achieve usability, big data systems still needed to learn from mature database experiences.

Encounter: The Rapid Rise of Apache Spark, Databricks’ Marketing Savvy, and Microsoft’s Internal Big Data Technology Stack

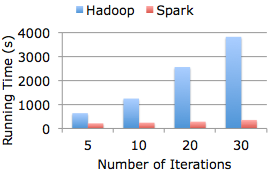

I still remember the scene in the fall of 2013 when Reynold Xin brought that “Spark system 100 times faster than Hadoop” promotional display to our department for a presentation. Someone asked whether naming it this way was too clickbait since most scenarios couldn’t achieve such high performance optimization. Looking back now, Databricks was indeed very skilled at technical marketing. Their later rivalry with Flink and public disputes with Snowflake were not surprising.

When I first encountered Spark, I was immediately attracted by its strong academic style and better usability compared to Hadoop. In my view, it had the following characteristics:

- User-friendly API. Compared to MapReduce’s primitive API, richer operators could greatly improve usability, reduce code lines, and avoid the pain of reinventing the wheel.

- The introduction of DAG enabled many shuffle optimizations, shortening runtime.

- Memory caching of partial data could achieve obvious performance improvements in iterative machine learning scenarios.

- Developed using Scala language with many syntactic sugars, very cool. But from today’s perspective, Scala keeps adding new features without a pragmatic and maintainable attitude, even abandoning binary compatibility between major versions. The language itself is still filled with academic and experimental characteristics. It’s debatable whether Spark binding to Scala is still a good thing now. (The Flink community has already planned to abandon Scala)

In 2014, machine learning and AI concepts were experiencing a resurgence. Our lab, thinking that many underlying computing logics in machine learning were matrix operations, developed a distributed matrix computing library called Marlin using Spark combined with mature scientific computing libraries. Later, my senior labmate shared this at the third Spark Beijing meetup. Hucheng, who was using Spark for distributed machine learning algorithms at Microsoft Research Asia, saw this talk and invited us to intern at Microsoft. Since I was an immersive legitimate Xbox player at the time, I was very happy to get the internship opportunity. It might be the happiest time I’ve accepted an offer throughout my working career.

At the end of 2014, I took the train to Beijing for a six-month internship. During this time, I began to encounter large enterprise non-open source big data system solutions: Microsoft’s Cosmos and SCOPE. The former can be understood as Hadoop, while the latter can be understood as a more user-friendly Hive combined with the C# environment. The data volume it carried and the user-friendly SQL-like queries were beyond what the open-source Hadoop ecosystem could achieve at the time. This also made me realize that open source shouldn’t be the only criterion. In fact, large domestic internet companies, especially those with requirements for distributed storage, have their own self-developed systems or modified HDFS to meet larger data volume requirements. By the way, in 2015, Zhou Jingren, who was leading SCOPE, jumped ship to Alibaba, which was quite shocking news within the company at the time and is also a microcosm of talent flow between Chinese tech circles in China and the US.

During my internship, there was also a discussion that, due to my incomplete understanding of the essence at the time, looking back now, it was essentially about unified stream-batch processing: When my mentor was using Spark to implement algorithms like LDA, he was dissatisfied with Spark’s stage-cut execution method where some slow nodes’ shuffle writes were too slow, causing machine learning speeds to fall short of expectations. He asked me whether the various stages in Spark could execute like a pipeline. At the time, I thought this would require too significant modifications to Spark’s overall data exchange architecture and would be inconvenient to modify. Actually, the essence of this problem was Flink’s blocking vs pipeline shuffle, which was later addressed in newer Flink versions with hybrid shuffle. We’ll elaborate on this below.

Later, we organized our ideas based on that distributed matrix library concept into a paper that was accepted by IEEE TPDS, a CCF-A class journal, leaving a footprint in my brief academic career. So I’m still very grateful to Spark - without this system, it would have been difficult to have the foundation tools for this paper.

Struggling: Spark Streaming, Love You But Can’t Have You

After the internship ended, I successfully received a formal offer from Microsoft’s shared data group, beginning my working life journey. As mentioned earlier, because Microsoft Beijing’s shared data group provided venues for several Spark Beijing meetups, the reason was that the group provided Spark clusters on a bunch of Windows machines running Autopilot (similar to k8s deployment system) within the company, hoping to enhance its influence within the company through the hot open-source activities. Unfortunately, due to the company’s very powerful Cosmos ecosystem, Spark didn’t show advantages in large-scale data processing compared to it, so the French PM in the group would focus on promoting this system for 1-100TB scale data processing within minutes. Even so, promotion within the company was still struggling. Fortunately, the group soon found an area that Cosmos hadn’t touched: real-time computing. So after I started working, I was mainly struggling with Spark streaming. The reasons for calling it struggling were as follows:

- There was no good backpressure mechanism. When data surged, memory would surge, and Spark clusters would easily crash. Since real-time jobs theoretically run continuously, I remember that it was difficult for any job to run stably for more than a month at the time.

- There was no incremental checkpoint mechanism. When the data scale became large, the entire distributed RDD needed to be persisted for checkpointing, making the system very unstable.

- Spark clusters ran on Windows environment, always encountering some strange problems. This wasn’t Spark’s fault; it’s just that Microsoft Bing’s deployment environment at the time wasn’t very compatible with the open-source ecosystem.

With system instability and limited business promotion, naturally, I wasn’t happy working. At that time, I always felt like a small screw in Microsoft’s huge wheel. The core systems were controlled by the US headquarters, and I could only do some side jobs. The department manager Haitao had a classmate relationship with Jiang Xiaowei (alias Liangzai), the head of Alibaba’s computing platform division’s real-time computing department. Later, he also jumped ship to Alibaba to work on the Blink system that had just launched. So when I was on vacation in Japan in early summer 2017, the moment I received Haitao’s “poaching” WeChat message, I immediately and readily agreed, not for other reasons, but simply because I wanted to work on the most core systems in a large company.

Full Commitment: Blink & Flink, A Glimpse of Brilliance

Blink literally means “blink” and is Alibaba’s large-scale secondary development real-time computing system based on Apache Flink. Regarding why Alibaba chose to base its technical selection and iteration on Flink despite already having three real-time computing systems internally - JStorm, Galaxy, and iStream - there are actually many articles online by the two successive main leaders of the real-time computing department, Jiang Xiaowei and Wang Feng (alias Mo Wen), describing this process, so I won’t expand here. I have to say, the technical foresight of the predecessors is admirable.

After joining Alibaba, my first shock was that Alibaba already had Blink jobs running stably for over a year, which was undoubtedly a qualitative leap compared to the situation where Spark streaming could barely run for over a month. I was responsible for state-related development in the Blink real-time computing engine. If we compare this to batch processing, it’s essentially about implementing aggregation logic in the map-reduce stage using local storage. I think the reasons why Flink’s streaming computing engine (including the later restructured Spark structured streaming) can be stronger than Spark’s are mainly the following points:

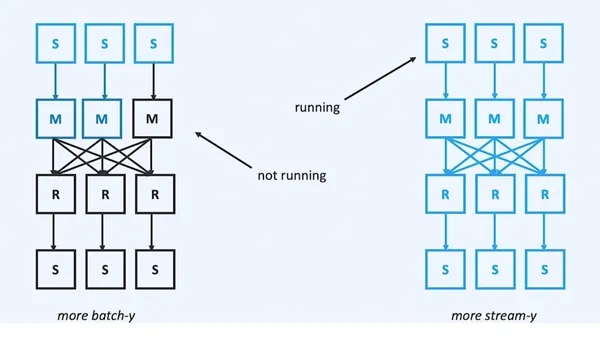

- Different design concepts bring different latency ceilings. Flink is streaming-first, so the operators of streaming jobs run continuously after obtaining resources. This allows for pipeline data transmission between operators, naturally achieving millisecond-level latency. Spark, on the other hand, builds streaming computing on a batch engine with a micro-batch architecture. Its operators still cut stages during map-reduce, so the next stage can only execute after the previous stage completes, naturally unable to achieve millisecond-level latency. Of course, this has some benefits. In situations where acceptable latency is possible, it can save some resources (since operators aren’t always running). The figure below comes from an article Aljoscha wrote when doing API restructuring. When you’re more oriented toward streaming computing, you should apply for more resources to keep operators running:

- Different design concepts bring different shuffle implementations. Spark’s shuffle comes from MapReduce’s classic theory, where data transmission is cut into classic two phases: map-side disk writing and reduce-side disk reading based on key partitioning. The benefit is simple and stable implementation. Flink, being streaming-first, uses a pipeline mode where data transmission is directly connected through upstream and downstream task network buffers. The aggregation logic is mainly processed in the downstream reduce side (in Flink, this is the keyBy operator). The benefit is achieving low latency, but the downside is that the state implementation is more complex. Especially to achieve low latency, the state backend needs to make a trade-off between performance and capacity, which is why large-scale real-time jobs need to use RocksDB state-backend to solve the stability issues of on-heap memory-based state-backends. Another significant advantage of Flink’s data exchange method is the natural implementation of backpressure mechanism. The network data buffer queues between upstream and downstream tasks form a classic producer-consumer model. When the downstream’s consumption capacity is insufficient, the downstream cannot place data into the buffer queue, forming a backpressure state for the entire job, preventing continued data consumption from the source and avoiding job instability due to data surges. Spark still lacks a complete backpressure mechanism to improve stability.

- Lighter checkpoint mechanism. The restructured Spark structured streaming also introduced state to avoid the instability caused by persisting entire RDDs in the old version of Spark streaming. However, due to the micro-batch mechanism, these states still need to be committed and persisted at the end of each batch when checkpointing is enabled, unlike Flink’s async checkpoint barrier, which can perform lightweight checkpoints at any time. This was one of Flink’s early highlights in the academic circle.

In 2018, with the convening of Flink Forward Asia, Alibaba also began preparing to acquire the startup company data-artisans behind Flink, finally acquiring it for 90 million euros in early 2019 and renaming it Ververica. At that time, we thought this money was well spent. After Alibaba acquired Ververica, it began the path of integrating enterprise and community versions, including donating Blink (we had iterated to Blink-3.x internally) to the Flink community, collaborating with the German team to create the enterprise version Ververica Platform, and so on. At the time, many people were somewhat worried that these European friends might, like many open-source technology companies, start a second venture, causing Alibaba to waste money. There are many stories here, and I’ll write articles about them if I have the opportunity in the future.

In 2020, I also finally became an Apache Flink committer, mainly responsible for Flink state & checkpoint related modules.

New Chapter: Why Now is the Time to Promote Large-Scale Adoption of Flink’s Unified Stream-Batch Processing Engines

In 2022, I left Alibaba, where I had worked for nearly five years, for personal reasons, moved to another city, and began another journey in my career. My focus shifted from Flink streaming processing state and fault tolerance to the entire Flink system. Here, I will tentatively answer the following questions to explain why I believe now is the time to promote large-scale adoption of Flink’s unified stream-batch processing engines.

What Can Unified Stream-Batch Processing Engines Bring

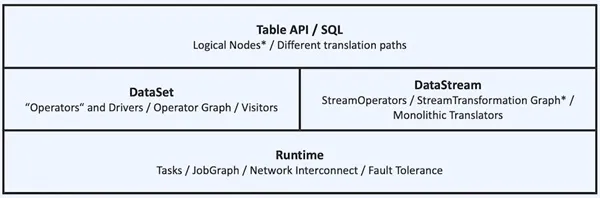

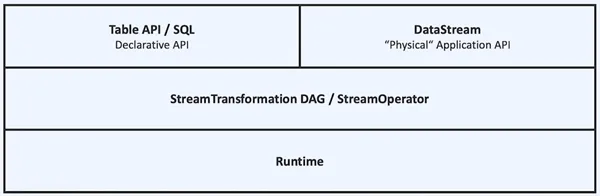

In Flink’s early papers, it also claimed to be “Stream and Batch Processing in a Single Engine,” but in reality, the two were actually two different sets of APIs: DataSet and DataStream (see figure below). For users, except for reducing the maintenance of a set of clusters, the coding experience is completely different, unable to maximize value in enterprises.

With Blink being donated to the Flink community, Liangzai’s vision of “unified stream-batch” computing engines that he envisioned in 2015 began the restructuring journey. Currently, with the DataSet API being deprecated, the current API architecture is as shown in the figure below; for users, by using a unified DataStream or Table API, one set of code can implement batch processing and streaming processing optimized jobs (most can automatically infer execution mode through source). This reduces the technical stack that needs to be maintained, reduces the pressure of data caliber alignment, and greatly improves development efficiency. Especially in stream-batch fusion scenarios, such as index data generation scenarios, which require both previous full data and real-time data indexing, one set of APIs can greatly improve development efficiency.

Why Flink is Suitable for This Unified Stream-Batch Engine

The previous discussion has actually covered many differences between streaming and batch computing. In streaming computing, to achieve aggregation calculations that are taken for granted in batch processing under low latency conditions, mechanisms such as state, changelog streams, lightweight asynchronous checkpoint fault tolerance supporting exactly-once, watermarks, backpressure, and pipeline shuffle have been introduced. It can be simply understood that designing and implementing the Flink system requires considering more complex problems, so when it “downgrades” to be compatible with batch processing, it forms a kind of overwhelming advantage. Therefore, when the Flink community can finally spare effort to enhance the batch engine, it naturally becomes a natural progression. In the current open-source solutions, Flink has become the de facto standard for real-time computing, and its focus on enhancing the batch engine is naturally the most suitable.

To What Extent Has Flink’s Unified Stream-Batch Processing Achieved

In my opinion, an excellent batch engine facing the current big data ecosystem needs to be involved in shuffle capabilities, complex SQL parsing, Hive compatibility, out-of-the-box usability, and execution performance:

- Shuffle capabilities: Flink’s batch mode shuffle followed a development path similar to Spark, first implementing hash-based shuffle strategies, then implementing sort-based shuffle strategies in Flink-1.13, which officially became the default strategy in Flink-1.15. I seem to see the historical process of the Spark community introducing sort shuffle in 2014 and finally dropping hash shuffle in 2016. Flink also completed the remote shuffle service capability and introduced hybrid shuffle as a new feature for stream-batch fusion in Flink-1.16.

- Complex SQL parsing: The currently feature-frozen flink-1.17 and Spark-3.3 SQL-related feature comparison can refer to the document Feature Comparison: Flink Batch vs Spark Batch, which generally shows a trend of catching up in functionality.

- Hive compatibility: The Flink community supports Hive dialect and related Hive ecosystem enhancements, with compatibility reaching about 94% on hive qtest.

- Out-of-the-box usability: Flink-1.15 introduced adaptive batch scheduler, which can adaptively determine the job concurrency, eliminating the hassle of manual configuration.

- Execution performance: Flink-1.16 introduced speculative execution mechanism to avoid performance impacts from slow nodes. Currently, test performance on TPC-DS is close to open-source Spark, with the basic goal in Flink-1.18 being that 80% of queries can reach or exceed Spark’s performance. The Flink community is also exploring with the Velox community to explore the possibility of implementing a native engine.

Currently in the industry, companies such as Alibaba, ByteDance, Ant Group, Kuaishou, and Shopee already have thousands to tens of thousands of Flink batch jobs running online. From the above comparison, it can be seen that the Flink community still has some work to complete in this area, so joining the Flink community for related development is a good timing. So now is the time to promote large-scale adoption of unified stream-batch processing engines!

Promoting Flink Stream-Batch Unification Landing, the Open Source Community is Taking Action

Currently, the Flink community has also created a flink-sync google group, holding Flink batch meetings every other Wednesday, discussing the Flink Batch roadmap on February 22nd, welcome to participate!

References

- MapReduce: A Huge Step Backward https://courses.cs.washington.edu/courses/csep544/21sp/papers/map-reduce-step-backwards-2008.pdf

- Databricks Challenges Flink https://www.databricks.com/blog/2017/10/11/benchmarking-structured-streaming-on-databricks-runtime-against-state-of-the-art-streaming-systems.html

- Flink反击Databricks https://www.ververica.com/blog/curious-case-broken-benchmark-revisiting-apache-flink-vs-databricks-runtime

- Databricks: Eliminating Database Benchmark Anti-Competitive Clauses https://www.databricks.com/blog/2021/11/08/eliminating-the-dewitt-clause-for-database-benchmarking.html

- Snowflake: Industry Benchmark Integrity Competition https://www.snowflake.com/blog/industry-benchmarks-and-competing-with-integrity/

- FLIP-256: Drop Scala API https://cwiki.apache.org/confluence/display/FLINK/FLIP-265+Deprecate+and+remove+Scala+API+support

- BLAS https://netlib.org/blas/

- 基于Spark的分布式矩阵计算库, 这个名字与Matrix前两个字母相同, 其本意"枪鱼"感觉也比较酷 https://github.com/pasalab/marlin

- Improving Execution Concurrency of Large-Scale Matrix Multiplication on Distributed Data-Parallel Platforms https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7884988

- 量仔的Blink之旅 https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/54262989

- Flink推动者莫问: 扛过三年双11, 团队半年贡献120万行开源代码 https://www.infoq.cn/article/KgJITFdbhXwI53QFRY3j

- 重新思考Flink的API https://www.infoq.com/articles/rethinking-flink-api/

- VLDB'2017 state management in Flink https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/State-Management-in-Apache-Flink%C2%AE%3A-Consistent-Carbone-Ewen/6fa0917412ab8db6c939ec671bc1f74d6655f465

- Stream and Batch Processing in a Single Engine https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Apache-Flink%E2%84%A2%3A-Stream-and-Batch-Processing-in-a-Carbone-Katsifodimos/ab18dc8b12ab8db6c939ec671bc1f74d6655f465